Financial Sentiment Fails to Predict the Stock Market

Is watching CNBC hazardous to your wealth?

How it started

Last summer I was sitting in a hotel room in San Diego, watching CNBC, which is the channel I find most tolerable when I'm stuck watching cable.

I watch CNBC regularly at the gym and for months I'd seen the financial news and the markets seem to move independently of one another, an intuition that has held up throughout the last year, where the U.S. stock market has put up heavy gains despite madcap politics, jitters about Fed policy, occasional international shockwaves, never mind random nonsensical advice such as "sell in May and go away" and chartists who go unquestioned when they say "You shouldn't buy CREE now as 60, but you should buy it later at 64."

It's often said, however, that markets are driven by fear and greed and that the Dow Jones Average is a sort of "emotional barometer" about people's feeling about our economic prospects.

Although companies such as Alchemy API and http://www.openamplify.com/ offer a free tier of access to APIs that include sentiment analysis, I hadn't seen a demo that was actually cool and I thought an analysis of the financial press would be interesting

Defining the FSI

I created the FSI with a small set of PHP scripts; two ran as cron jobs, one that harvested nearly 1000 articles a day from Yahoo Finance RSS feeds and ran them through a popular sentiment analysis API. (The 1000 article limit was set by the 1000 API call limit from the free tier of the API, which will go unnamed.)

For each article, the API returned a "positive" or "negative" opinion and a numeric confidence score which was positive for positive sentiment and negative for negative sentiment.

I performed an evaluation of the sentiment analyzer that involved my judging the positive and negative sentiment of roughly 1000 articles. I used the result to create a linear transformation that made the score published on the FSI an estimator that a chosen article, on a given day, was positive or negative in sentiment.

Failure to predict

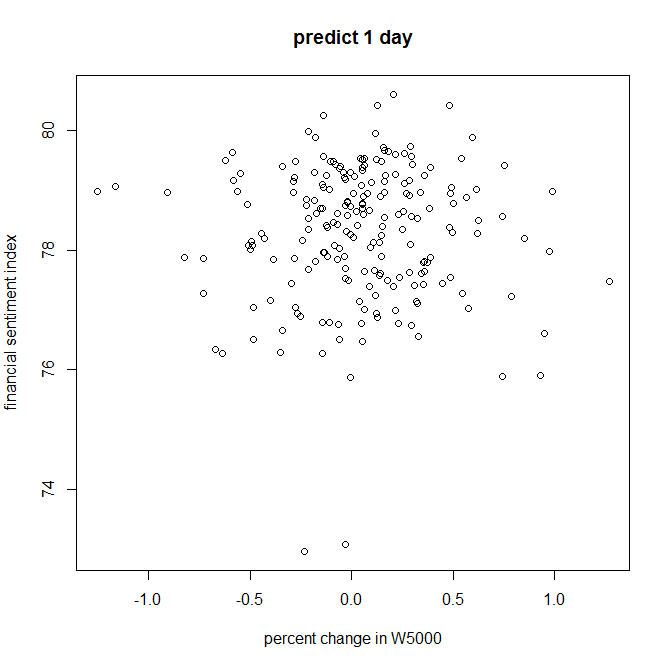

The following graph is a plot of the percentage change of the Wilshire 5000 index between the open on one morning (when the FSI is computed) to open on the next trading day. This measure is sensitive to price changes that happen during both the trading day and during the aftermarket.

Here we get a correlation coefficients of -0.00360 (Pearson), 0.00756 (Kendall) and 0.00989 (Spearman), all of which are tiny, pointing to a patient which is dead on arrival. The FSI has no value at predicting the Wilshire 5000 index, which is quite similar to the S&P 500 index except that it is broader, covering all tradable stocks.

What about retrodiction?

We know that predicting the stock market is at the very least difficult and some say impossible. It ought to be possible, however, to read articles and determine what direction the market moved yesterday, simply because you'll find many articles that specifically say in what direction and how far popular indexes such as the S&P 500, Dow Jones Index and NASDAQ 100 have moved.

Now, our algorithm is not that specific, but let's see how the FSI correlates to the difference between yesterday's open and today's open:

The correlation coefficients are consistently positive and larger than the last one, but still below the threshold for statistical significance: Pearson 0.0510 (p-value: 0.4625), Spearman 0.104 (p-value: 0.1294) and Kendall 0.074 (p-value: 0.1111).

The FSI, as it exists, is not useful for retrodiction.

Could this possibly work?

When I tell people about this, they ask me "Did you think this could possibly work?"

The literature on the subject is highly skeptical about trading on the news, and a good account of this in Norman Fosback's classic book "Stock Market Logic."

Fundamentally, markets react quickly to news, so if you see something in the news and want to trade it, you'll probably find the market has moved substantially against you. (Try it!)

One answer to this is to "buy the rumor and sell the news," which is a sane sort of speculation. Another one is to react incredibly quickly to the news, as some high frequency traders do -- if market makers can at all get away with it, they 'll certainly want to get out of the way of any volatility. Another approach is to trade the news before it becomes news, with the small problem that this is illegal.

Can the FSI be improved?

Certainly. In this project I learned many things that would be necessary for any real application of text analysis to financial markets.

Timing matters: often there is ambiguity between when a news event happens, when the story is covered (by different outlets) and when the news is picked up by the recording system. This source of error can be serious and needs to be controlled

Financial sentiment is not the same as emotional tone: a sentiment analyzer can perform better when it is tuned to a particular domain. A sentiment analyzer trained on movie reviews wouldn't learn that a buy recommendation is positive or that a sell recommendation is negative.

Noise: many pundits regularly issue, say, five buy recommendations and five sell recommendations a week. It's clear that a count of these has no information content, in fact, it's not clear that public stock tipsters say anything worth listening to.

If I were to develop a sequel to the FSI, I'd be interested in building a set of machine learning algorithm that, given an news item, tries to predict or retrodict price movements of individal items over multiple fixed intervals. The advantage here is that one can dispense with expensive human judgments for training and replace them with the cheap and presumably authoritative judgements of the ticker.

What should an investor do? Stop trading

If you believe a strong version of the efficient market hypothesis, your best bet is to invest in inexpensive index funds. Even if you can't predict the stock market, you can predict that each cycle of buying and selling can cost you 1-3% of the value of your investment between commissions, the bid-ask spread and other costs of trading.

The financial services firms that sponsor CNBC, the Wall Street Journal, and other news sources profit when you trade; since trading costs money and eats into returns, it only makes sense to trade when you've got a strong reason to believe you can earn more than the "friction" in the system. One of the best things you can do to protect your wealth is to stop trading the news, and not go "risk on" and "risk off" as the drop of a hat. The biggest losers of the last decade were people who panicked after the 2008 crash and sold at the bottom; it's hard to say how to be a winner, but it's easy to avoid being a loser.

Creator of database animals and bayesian brains